By Melissa Dahl

In the five days since the plane disappeared, these loved ones have been in anguished limbo — a state known as "ambiguous loss," coined by psychologist and author Pauline Boss.

“That is, when somebody is missing or has vanished without a trace, and you don’t know their fate, or the whereabouts of their body, and whether they’re dead or alive,” Boss says. “So it becomes so uncanny, and strange, for the families; they’re never quite sure if the person is truly dead.”

It’s a feeling that can apply to dozens of experiences, like losing a pregnancy, or losing a family member, small pieces at a time, to Alzheimer’s or dementia. And it also applies to the families of the missing: missing children, missing persons, or soldiers missing in action.

“It is the worst kind of loss to process — I don’t mean to say one kind of loss is worse than another. But this is the kind of loss that creates suffering without closure,” Boss said. “There is no closure, ever, if bodies can’t be found.”

One afternoon in Omaha, Kelly Murphy’s 19-year-old son, Jason Jolkowski, left their home to head to work. His little brother saw him leave the house, and neighbors saw him walking to his old high school, where a co-worker planned to meet him in order to give him a ride.

“And that was the last anyone ever saw him,” says Murphy. “He literally just disappeared off the face of the earth. It’s been 12 years and we really don’t know anything more than we did on day one.” She says that usually, families in this situation have something to work with: a violent boyfriend, an estranged parent, a missing jetliner. “But this one, there’s just absolutely nothing. And that makes it harder; you have nothing to go on.”

"You go through partial stages of grief but you can’t go through all the stages. You don’t know what you’re grieving for."

Part of the reason that ambiguous loss might be so taxing on a person is the fact that our brains crave information. Some scientists have posed the theory that humans are, innately, information-seeking creatures; we need answers, we need closure and we need an ending. “It becomes a problem of cognition. It’s actually difficult for the brain to process this loss because there is no information about it,” Boss says.

“You go through partial stages of grief but you can’t go through all the stages. You don’t know what you’re grieving for,” Murphy says. She’s been reading the stories of the families of the Malaysia Airlines passengers calling their loved ones’ cell phones; in the days and weeks after Jason disappeared, she did the same thing with Jason’s phone.

“So I can relate to what they’re going through. You want to cling to hope,” Murphy says. “But as the days pass, I’m sure that, in their logical minds, they know, this doesn’t look good. What I hope for them is that they find some answers that give them some sort of peace.”

Because after a death, there are a prescribed set of rituals, according to your culture: throwing a handful of dirt on the coffin, or spreading the ashes in a favorite place of the deceased. All of these rituals have a purpose, helping the person process the grief. But with the missing — when a person is simply, mysteriously gone — the people left behind are helpless. Any ritual or burial or memorial has to be purely symbolic.

This was Sue Scott’s life for 45 years, since Dec. 30, 1969, when her brother’s plane went missing in Laos.

“Even though the flame of hope is so minute after so many years, you never quite give that up,” Scott said. “I think you’re always hoping for them to walk through the door. I don’t think that ever goes away. Some miracle will happen and they will walk through the door.”

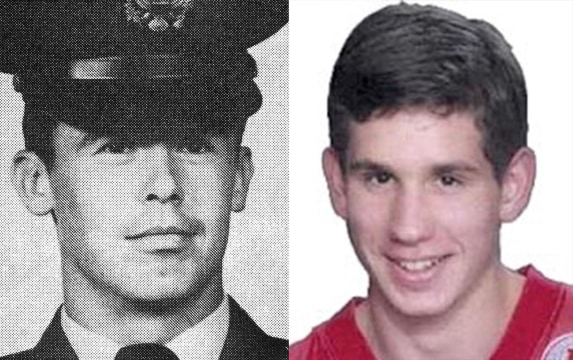

Courtesy of Sue Scott; Kelly Murphy

Courtesy of Sue Scott; Kelly Murphy

Little bits of information trickled in over the last four decades about Captain Doug Ferguson: Investigators found his crash site. They learned that he died holding off the enemy, while two pilots were rescued. Later, they found pieces of his plane. And then, confirmed just last week — they found him. Ferguson’s remains were finally found and identified, Scott said.

“Many had said that it was really gut-wrenching. So I didn’t know what to expect,” Scott said of when she heard the news last week. “But, actually, I felt a sense of peace as a result.

“For me, in some sense, it was a sense of relief, to finally be able to move forward. And I don’t mean ‘get on with my life.’ What I mean is to celebrate his life,” Scott said.

Scott got her answer, and Captain Doug Ferguson will finally be coming home to Tacoma, Wash., on May 1, to be buried. Her story has a concrete ending.

Murphy’s, after more than a decade, still doesn’t. So she’s learned to “live in the not-knowing,” as she calls it. It’s not something she’ll ever “get over,” and she’s not interested in that, anyway. She’s channeled her grief over Jason’s disappearance into the formation of Project Jason, a nonprofit that provides support for missing persons.

“They will grieve off and on for the rest of their lives, and this is normal,” Boss says. “There is no closure on ambiguous loss, and we need to acknowledge that. It’s OK to not get over it; that’s OK even with an ordinary death.”

First published

March 12th 2014, 3:52 pm

No comments:

Post a Comment